How to spot end game Mozart Piano Playing

Musicians nearly unanimously refer to Mozart as the hardest composer to master. He requires the highest agility to play, physically and mentally.

I think the majority of Mozart players who fail at Mozart fail mentally. Logically there is no other explanation as we have heard them convincingly play much harder works. Listening to masterful Mozart playing is among my joys in life. Here are some discoveries I’ve made as to what you are actually hearing when you hear “good” Mozart on the piano.

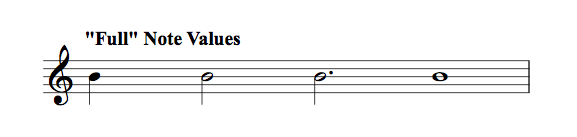

Smoothness and Long Phrases in Mozart:

Mozart requires the pianist to compensate for the natural tendencies of the fingers and instrument.

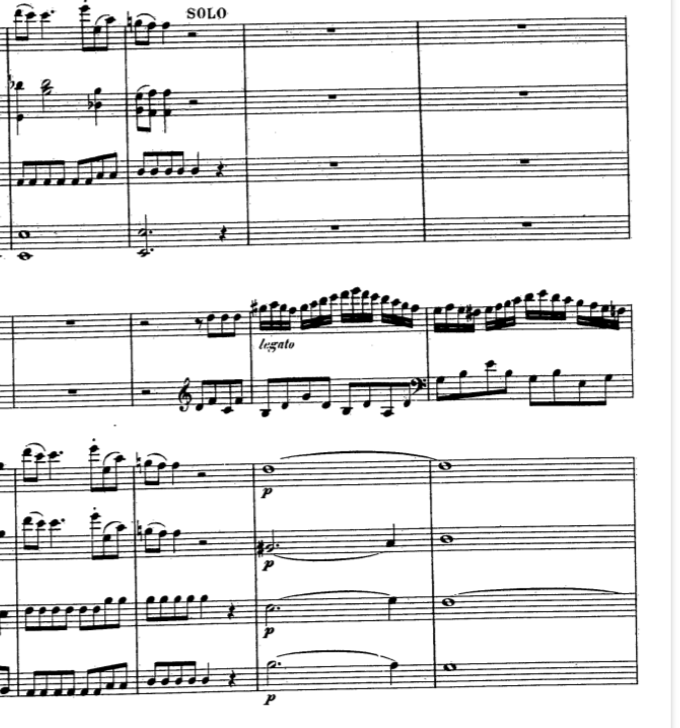

For example in this excerpt (above) the piano will want to crescendo on the the bar marked “legato”.

The pianist must resist this and remain neutral in order to play the long phrase (all of the 16th notes are one phrase).

The fingers will also want to set anchor points where the direction of the scales change but this too must be resisted. The line needs to be continuously gradual.

It takes a bit of sustained effort and compensating to do this.

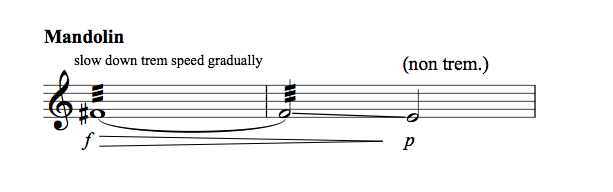

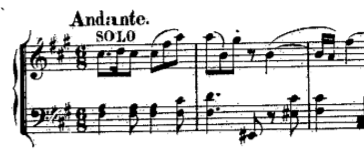

In this phrase (above) the fingers want to bring out the 1-4 (downwards) and 4-1 (upwards) finger connections but the brain must resist it.

The fingers also want to set the E natural (the second note of the second bar RH) as an anchor point of a large scale but the brain must resist it and place it dynamically appropriately.

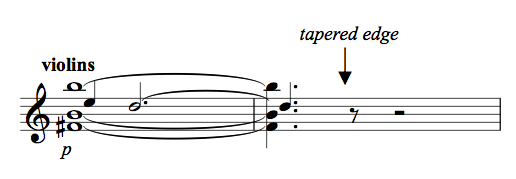

Listening To The Instrument

Slow movement Mozart often requires the pianist to be aware of the decay of the piano and to align the dynamics of the new notes to match the decay of the old note. This is the truest form of decrescendo/legato on the instrument which has no true monophonic legato.

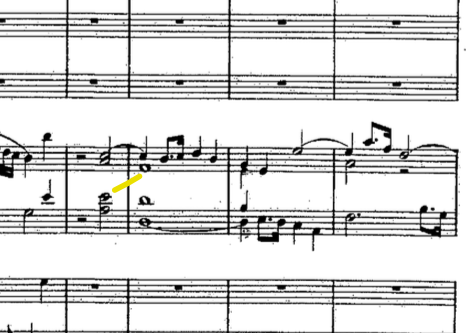

In this example (right) the low E# in the left hand has the tendency to punctuate the texture and interrupt the right hand melody which despite having a rest appears as one long line.

Sensitive pianists will listen to the decay of the F#/D chord and place the E# in that same area (which is really contrary to what the fingers want to naturally do – they want to play it heavier).

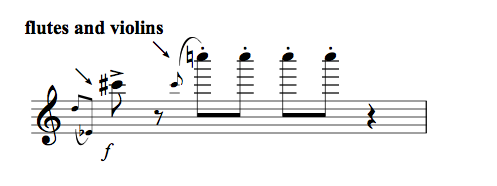

There are also times where the hands are equal partners.

What is the more likely rhythmic motif of the right excerpt – continuous sixteenth notes? or a sixteen rest followed by three sixteenth notes?

It is A for me – continuous sixteenths – which hand the motif is played on is secondary – it doesn’t matter.

There are also times where taste comes in.

Out of all the moving voices in this A to D major chord passage I think the yellow line is the prettiest.

Orchestral Awareness

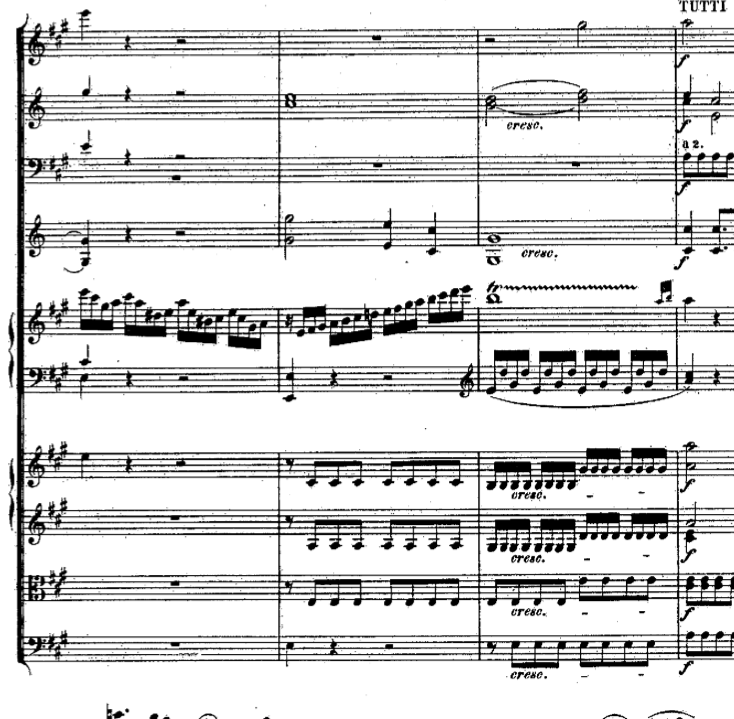

Another thing I notice is high level Mozart is that the pianist is obviously aware of the accompaniment.

Most pianists anchor this low E (second bar) octave seemingly unaware that it is part of the blooming French Horn line which blooms more convincingly if the piano doesn’t obliterate them on the first beat.

Sometimes you hear a pianist using a “pizzicato” touch when doing trading passages with pizzing low strings.