A Chart/Concept to Keep Your Listeners Interested

When a viewer observes a painting there is a “oh, well there it is” moment when the frame is first presented – it is first taken in as a whole and then the details are discovered upon closer examination.

Music is also largely in the moment – details first – and then the whole comes second if it comes at all. The conclusion of Tosca is powerful in the moment (due to it’s orchestration and setting) but even more powerful after sitting through a two hour love story.

Keep in mind that only the best listeners (maybe 10%) have access to musical recall upon a first hearing. During a first listening the average listener is sort of engulfed in a vague musical energy rather than any concrete quasi-analytical musical experience (where they recognize form for example). It takes many listens to achieve that sort of familiarity with the piece. Regardless of the language you use they will like or dislike the piece based upon how convincingly you executed your plan.

All of my personal favorite composers not only engage on the whole but also “live” or in the instant. Mozart does this over-the-whole by developing and bringing back old material, and live by using beautiful suspensions, tasty melodies and clever counterpoint. You are satisfied twice. I currently dislike Mahler ( I hope to learn to like him) because it is all too much in the moment, there is a lack of arrival and departure points (sensical musical architecture). PS. I know Mahler did this on purpose, and he is a wonderful composer of course – just not my favorite.

I think clever is the key word here. It takes cleverness to impress. Just the way a clever author leaves a climax at the end of a chapter, and you turn the page with all possible speed.

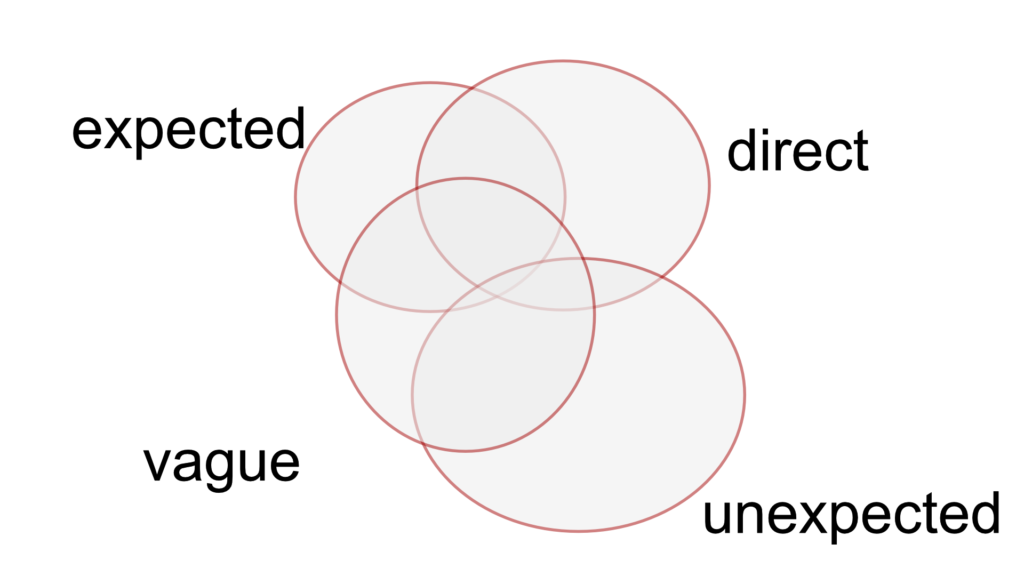

Here is a chart I made – its a “to scale” Venn-Diagram for what I consider “modern classical music”.

Inside this chart you really want to stick to the middle – occasionally venturing in a direction that departs from the center point, but always back to the middle then out again. Back and forth, give and take.

Consider if you go too far in any one direction, you risk disappointing:

too “expected” becomes overly-simple and boring

too “vague” leads to scratched heads (and not in that “good way”)

too “direct” becomes overly-cinematic and not-classical

too “unexpected” starts to sound like multiple pieces, instead of one

This chart is usable in any type of music, with any type of harmonic langue and parameters.

I find a lot of modern classical music overuses a Moderato tempo – and one becomes sick of it’s overly-expected energy level (whereas a fast or slow energy might break the monotony.)

Overly eclectic music often takes the unexpected too far – if we are in a Baroque-ish vibe and suddenly a steel drum solo breaks out it doesn’t often convince the listener that it’s one entity.

I find a lot of modern film music too direct – I’ve heard it all a million times before – start to zone out.

I find Enimem gives me a nice balance of all in terms of lyricism and music, the beat drops for a few beats, a clever lyric follows, a half-a-chorus follows that (instead of a full one) etc..

John Williams’ Prisoner of Azkaban score is very much in the middle of this graph, it has tons of unexpected energy but sounds like its all from one score.

And of course the Rite Of Spring is just about a perfect example of chart-management.

But mostly when composers are hitting in the middle of that chart they are at the ultimate top of their game for that particular piece. It is very, very hard to do.